![Dear Life]()

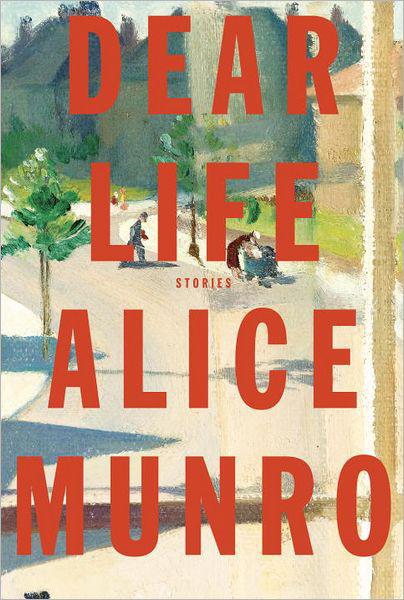

Dear Life

the kitchen door. As far as I know, it never had a proper lock. There was just a custom, at night, of pushing one of the kitchen chairs against that door, and tilting it with the chair back under the doorknob in such a way that anybody pushing it to get in would have made a dreadful clatter. A fairly haphazard way of maintaining safety, it seems to me, and not in keeping, either, with the fact that my father had a revolver in the house, in a desk drawer. Also, as was natural in the house of a man who regularly had to shoot horses, there was a rifle and a couple of shotguns. Unloaded, of course.

Did my mother think of any weapon, once she had got the doorknob wedged in place? Had she ever picked up a gun, or loaded one, in her life?

Did it cross her mind that the old woman might just be paying a neighborly visit? I don’t think so. There must have been a difference in the walk, a determination in theapproach of a woman who was not a visitor coming down the lane, not making a friendly approach down our road.

It is possible that my mother prayed, but never mentioned it.

She knew that there was an investigation of the blankets in the carriage, because, just before she pulled down the kitchen-door blind, she saw one of those blankets being flung out to land on the ground. After that, she did not try to get the blind down on any other window, but stayed with me in her arms in a corner where she could not be seen.

No decent knock on the door. But no pushing at the chair, either. No banging or rattling. My mother in the hiding place by the dumbwaiter, hoping against hope that the quiet meant the woman had changed her mind and gone home.

Not so. She was walking around the house, taking her time, and stopping at every downstairs window. The storm windows, of course, were not on now, in summer. She could press her face against every pane of glass. The blinds were all up as high as they could go, because of the fine day. The woman was not very tall, but she did not have to stretch to see inside.

How did my mother know this? It was not as if she were running around with me in her arms, hiding behind one piece of furniture after another, peering out, distraught with terror, to meet with the staring eyes and maybe a wild grin.

She stayed by the dumbwaiter. What else could she do?

There was the cellar, of course. The windows were too small for anybody to get through them. But there was no inside hook on the cellar door. And it would have been more horrible, somehow, to be trapped down there in the dark, if the woman did finally push her way into the house and came down the cellar steps.

There were also the rooms upstairs, but to get there mymother would have had to cross the big main room—that room where the beatings would take place in the future, but which lost its malevolence after the stairs were closed in.

I don’t know when my mother first told me this story, but it seems to me that that was where the earlier versions stopped—with Mrs. Netterfield pressing her face and hands against the glass while my mother hid. But in later versions there was an end to just looking. Impatience or anger took hold and then the rattling and the banging came. No mention of yelling. The old woman may not have had the breath to do it. Or perhaps she forgot what it was she’d come for, once her strength ran out.

Anyway, she gave up; that was all she did. After she had made her tour of all the windows and doors, she went away. My mother finally got the nerve to look around in the silence and concluded that Mrs. Netterfield had gone somewhere else.

She did not, however, take the chair away from the doorknob until my father came home.

I don’t mean to imply that my mother spoke of this often. It was not part of the repertoire that I got to know and, for the most part, found interesting. Her struggle to get to high school. The school where she taught, in Alberta, and where the children arrived on horseback. The friends she had at normal school, the innocent tricks that were played.

I could always make out what she was saying, though often, after her voice got thick, other people couldn’t. I was her interpreter, and sometimes I was full of misery when I had to repeat elaborate phrases or what she thought were jokes, and I could see that the nice people who stopped to talk were dying to get away.

The visitation of old Mrs. Netterfield, as she called it, wasnot something I was ever required to talk about. But I must have known

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher